How to Tune a Guitar

A guide on how to tune a Guitar. Follow the guitar string or skip ahead to your preferred subject by clicking How to Tune a Guitar by Ear or Other Things to Note.

How to use a Guitar Tuner

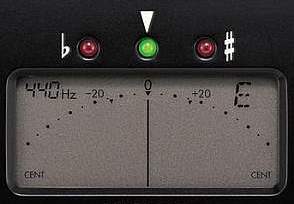

For accuracy it’s best to use an electronic guitar tuner. An electronic tuner can be plugged into an electric guitar and most also have a built in microphone so they can tune by sound and therefore also be used to tune acoustic guitars. Your guitar tuner should be set to 440Hz. On the KorgCA-30 shown in the picture this is indicated at the top left of its display.

440Hz is known as “Concert pitch” which means what sound frequency is defined as being the note of “A”, and that’s 440Hertz for 440 sound waves per second. On the KorgCA-30 this can be adjusted with the “calib” buttons (short for “calibrate”). If your guitar tuner has no indication of this then it will be set to concert pitch 440hz by default and can’t be altered.

Pluck the string at a moderate volume so the tuner can pick up the sound. If you aren’t plugged into the tuner you could rest the guitar on your lap with the tuner laid flat on the guitar to make it easier for the tuner’s microphone to pick up the sound. This also works for an un-amplified electric guitar or Bass.

This technique is similar to another kind of tuner, the clip on guitar tuner, which you clip onto your guitar. The clip on tuner, usually attached to the guitar’s head, picks up the vibrations that resonate through the guitar from the strings being plucked. Further below is a picture of a Korg Clip on tuner.

The Musical Alphabet

When you play any string the tuner’s display will show one of the following notes from the musical alphabet, as shown on the piano keys below. Many of the notes have two different names, such as D# and Eb which are the same note, or F# and Gb which are the same note (known as enharmonic equivalents). Notice also that all of the notes occur more than once. These are “octaves”, in simple terms that means the same note but at a higher or lower pitch. On the Piano diagram octaves of the note A and the note D# / Eb are highlighted as examples.

Tuning a Guitar

It is from the musical alphabet we need the guitar strings to be tuned to the notes E, A, D, G, B and E which is standard guitar tuning. This is shown on the fret-board picture below…

Let’s start by tuning the high E string. If you play this string and the tuner display does not say “E” then you need to adjust the tuning peg of the guitar so that it does.

A chromatic guitar tuner like the CA-30 detects all notes of the musical alphabet so if it says D or D#/Eb this would mean you need to tighten the high E string to raise its pitch until it says “E”. If it says F or F#/Gb then you need to loosen the string to make it lower until it says “E”.

How to Tune a Guitar by Ear

Tuning a guitar by ear can be less reliable if you don’t have good sound perception but can make good practise. There are two ways of doing this. The first and easiest of the two is to play the notes that you want to tune your guitar to on another device or instrument so that you can tune your guitar to it. Included are some links to different online tuners with the notes E, A, D, G, B, E for standard guitar tuning (as well as other tunings). You can also refer to the notes E, A, D, G,B, E on a piano or electronic keyboard for standard guitar tuning, or you could use pitch pipes. As long as the instrument you are tuning to is in tune itself.

Relative Tuning

This is tuning the guitar strings to each other. For this to work one string needs to be in tune already (usually the low E string) meaning you would need to use any of the previous methods to get this string in tune beforehand. The diagram shows how the strings relate to each other.

When you play the 5th fret of most of the strings, it gives the same note as the next string up played open. Providing that the low E string is in tune, we can play its 5th fret to give us the note of A and tune the open A string so it sounds the same. Once the A string is in tune, its 5th fret can then be used to tune the D string. You can work your way up through the strings tuning them in the same way.

The only exception to this method is the B string. Rather than being tuned to the 5th fret of the G string it needs to be tuned to the 4th fret of this string (this tuning makes “barre chords” possible). The different tuning of the B string can play an important role in understanding the layout of the fret-board and how you can move scale and chord shapes around it (if you know the chords open E, A and D major then there’s a clue in how they look different yet can be regarded as the same shape if you consider the B string)

A potential problem with the relative tuning method is the margin of human error might be times six by the time you have got to the high E string, so you would need good ears.

Other Things to Note

Bass Guitar: A Bass Guitar may not seem as likely to go out of tune, as all the strings are more sturdy and nickel wound, but the human ear is less tuned in to lower frequencies and it’s not always as easy to tell so it can be worth checking the tuning of your Bass. Standard tuning for a Bass is low E, A, D, G. A standard guitar tuner like the CA-30 an be used to tune a Bass.

Inertia: If you play the low E string reasonably hard around where the pickup near the fret-board is, you may notice the dial goes slightly sharp then settles. This is because of inertia, a physical body’s resistance to change of direction. In this case the strings initial resistance to the change of direction when plucked causes it to tighten slightly and make it go temporarily sharp. The more mass an object has (i.e. the thicker the string) the more inertia it has, so the Bass guitars strings can be affected. It can also apply to a lesser extent to the electric and acoustic guitar’s thicker strings. String inertia can lead to some confusion if tuning a guitar by ear.

This is worth bearing in mind if you are plucking a Bass loudly, inertia might be making the notes slightly sharp. Something that can reduce inertia while tuning (or playing) is to pluck the string away from its centre and closer to the bridge. Consider this when tuning by ear, it’s a subtlety that is not so easy to detect which is one reason I recommend an electronic tuner for accuracy.

Interesting fact: Humans are more tuned into mid-range frequencies (600Hz – 1.5Kz) which is why the Bass guitarist usually plays single note lines rather than chords, otherwise the notes would blend into each other and sound muddy.

Tuning a Nylon String Guitar

Because nylon strings are a bit more flexible and stretchy than metallic strings it can sometimes be best to tune upward so that you are tightening the string. If lowering a nylon string it could slip very slightly. If a guitar has only recently been strung with nylon strings this tends to be the case. Once newly strung, nylon strings will go flat for the first couple of days and need more tuning until they finally tighten. This mostly applies to the smoother G, B and high E strings. The lower strings of low E, A and D are usually metal wound so have more grip.

Harmonics & Intonation

The 12th fret of each string gives the same note as the open string an octave higher. Using harmonics on the 12th fret can be useful to tune with because they aren’t as affected by inertia and there is no potential for accidental string bend. Touch the string lightly with a fingertip directly above the fret (not behind as you usually would) then pluck the string with the other hand, once the harmonic is ringing you can take your finger away from the string and it will continue to ring.

Harmonics on the 12th fret (or for an even higher octave the 24th fret or where the 24th fret would be) can also be useful for judging your guitar’s intonation; the 12th fret should be the halfway point (quarter for 24th fret) between where the string comes out from the bridge and where it comes out from the nut on the guitar’s head. If an open string is in tune yet the harmonic on the 12th fret is different then your intonation might be out.

Varying Temperatures

If hot your guitar may sound flat, if cold it may sound sharp. It is best to keep your guitar at room temperature, which also avoids general damage that can occur over time from exposure to hot or cold temperatures.

Accidentally bending strings

When playing a chord, does something sound wrong like there is a string that is not quite in tune but you just can’t work out which? It might be your technique. You might be bending one of the strings slightly making it go sharp and clash with the rest of the chord.

A little less obvious is if it’s due to pushing the string down behind the 1st fret. The 1st fret being closer to the nut makes the angle more sheer when you push down. This is similar to the “behind the nut bend” technique when you push a string down behind the nut to bend it except in this case you are in front of the nut and you don’t want it! The higher your guitar’s action (how high the strings are elevated from the fret-board) the more acute this angle will be when pushing any string down on the 1st fret. For example for an E major chord it could be that you are applying a little too much pressure to the 1st fret G string making it slightly out of tune to the rest of the chord. Try applying a little less pressure with the 1st finger so that you are only pushing hard enough to get a clear note but not pushing the string down to the wood of the fret-board.